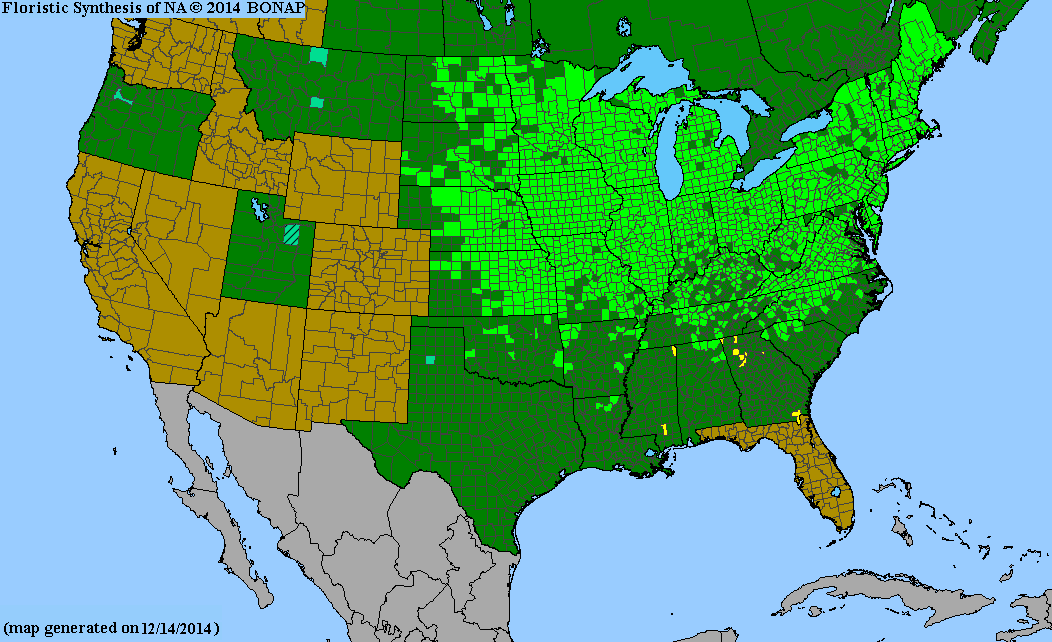

Chances are, if you grow any plant from the Carrot family (parsley, rue, celery, fennel, dill, golden alexander etc.) then may have seen this caterpillar eating on your plants or butterfly flitting around your garden!

|

AuthorRebecca Chandler Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed