Deadheading milkweed flowers in the early summer and cutting back old stalks in the fall are common ways to maintain a healthy milkweed patch!DeadheadingRemoving flowers that have wilted, also known as deadheading, is a great way to prolong blooms in the early and mid-summer. After the first flush of flowers, simply cut off the flower cluster above the topmost leaves on the stem. This will cause the plant to branch out and produce a second flush of flowers. Caution: The milkweed sap can be a skin irritant so be sure to use gloves while pruning. In order for your milkweed to be able to produce seed pods in the fall, deadhead only the first flush of flowers. A single milkweed plant will produce hundreds of seeds and it is the best way to ensure you have seeds for the following year! Learn more about milkweed seed saving here. Milkweed plants are known to spread so if you do not have room for more milkweed plants, cut the pods off in the fall when the pods are tan and the seeds are coffee brown. You can then give these seeds out to friends and family. Some birds are known to use the silky floss of milkweed pods to build their nests. The vermillion flycatcher, black-capped chickadees and Baltimore orioles are some of the known species that use milkweed floss for nest-building. So, once you have harvested seeds, you can toss the fluff back outside! Cut BackIt's always best to plant milkweeds that are native to your area. In Nebraska, we have 17 native varieties of milkweed. These native milkweed are perennials, meaning they come back year after year. Their aerial parts (flower, leaves, stem) die back but their rootstock remains alive throughout the winter. Cut back milkweed stalks in the late fall or winter, after they have produced seed pods and these seeds have had time to mature. Leave at least 6 inches of stalks to provide habitat for insects throughout the winter. Leaving stalks also gives you a marker so you know where your milkweed patch is. Birds such as Baltimore orioles can also strip fibers for nest material. When Spring arrives, you will have an abundance of new shoots and you won't have to do a thing! ResourcesBorders, Brianna and Lee-Mader, Eric. Milkweeds: A Conservation Practitioner's Guide

https://www.fws.gov/southwest/es/Documents/R2ES/Pollinators/8-Milkweeds_Handbook_XerSoc_June2014.pdf Dole, Claire Hagen. Brooklyn Botanic Garden. Milkweeds—Easing the Plight of the Monarch Butterfly. June 1, 2000. https://www.bbg.org/gardening/article/milkweeds#:~:text=Deadhead%20milkweed%20flowers%20to%20prolong,great%20in%20dried%2Dflower%20arrangements.

58 Comments

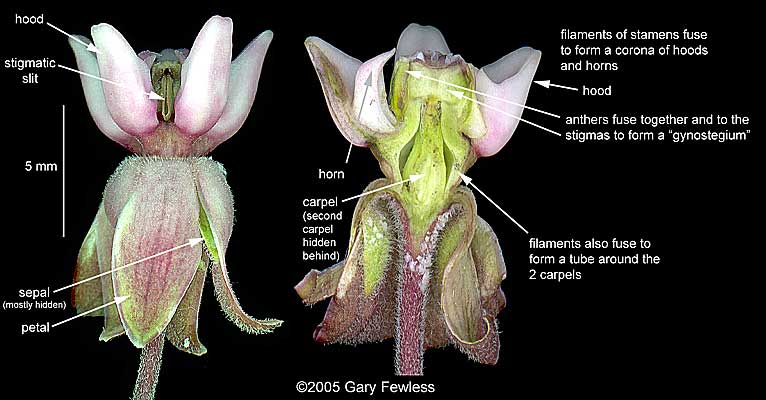

The story of an organism always leads beyond itself to a larger web of relations with other organisms and elements of the environment. There is no isolation in the living world." This summer, I have been studying my pollinator patch from the eye of a macro lens. To better understand the milkweed flower, I used a dissection kit to see the inner workings of this complex flower and was amazed at what I found! The story of the milkweed plant cannot be told without first discussing the numerous insects that rely on milkweed for food and shelter. A Hidden Chamber of Golden PollenMilkweed are not like most flowers and comparable only to orchids in the way that they store pollen. Most flowers release pollen from their showy anthers but milkweed keeps the pollen hidden within a stigmatic chamber. This chamber contains pollinia, or waxy masses of pollen grouped into golden pouches. The only way for the pollinia to escape these chambers is via insects. So, how does this mechanism work within milkweed flowers? As bees seek nectar that is found within the hoods of milkweed flowers, their legs may slip into the stigmatic slit of the milkweed flower which leads to the stigmatic chamber. When they pull their legs back out, they pull out the pollinia and carry it to other flowers, helping the milkweed to cross-pollinate. A study by Morse showed that a bumble bee picks up a new pollinarium every 2 to 5 hours. The pollinia will stay attached to the legs for an average of 2.5 hours and the mouthparts for an average of hours. So you see, plants can be clever too! The Structure of a Milkweed FlowerThis diagram will help you to better understand how milkweed and pollinators interact! The milkweed flower has 5 reflexed petals. Sitting atop the petals is a corona, or crown, which consists of 5 hoods and 5 horns. The hoods hold the nectar that attracts insects. Enclosed within the corona is a structure called the gynostegium, or stigmatic chamber. This reproductive chamber has 5 vertical slits called stigmatic slits around its perimeter. These slits allow access to the female ovaries and male pollinia within it. Coevolution of Milkweed and PollinatorsI can understand how a flower and a bee might slowly become, either simultaneously or one after the other, modified and adapted in the most perfect manner to each other, by the continued preservation of individuals presenting mutual and slightly favourable deviations of structure." There are various pollinating agents that plants utilize in order to reproduce. The way that milkweed plants "hide" their pollen inside these chambers may seem strange because most flowers carry their pollen on anthers outside of the flower. To understand why milkweeds do this, you have to look at the pollinating agents of milkweed. Pollinating agents are animals such as insects, birds, and bats; water; wind; and even plants themselves in the case of self- pollination. In this case, large bees, wasps, and butterflies are considered to be the most important pollinators of milkweed. Milkweeds pollination success is wholly dependent upon insects just as many insects are dependent upon milkweed for food and reproduction (Holdrege, 2010). An Evolutionary Arms Race“The process of coevolution between plants and their natural enemies — including viruses, fungi, bacteria, nematodes, insects and mammals — is believed by many biologists to have generated much of the Earth’s biological diversity” (Rausher, 2001, p. 857). Some researchers describe plant-pollinator relationships as a type of "arms race" that leads to more and more biodiversity on our planet. In his book, Monarch and Milkweed, Agrawal describes the relationship between monarchs and milkweed as a battle of exploitation and defense between two species. For instance, Milkweed developed a defense against predators called cardenolides, which is the white, latex that oozes out of milkweed leaves and also where milkweed got its name. Eventually the monarch larvae created their own defense to this toxic compound and began sequestering it into their bodies in order to become unpalatable and toxic to their predators. In ConclusionMilkweed fills a very important role from an ecological standpoint, especially for insect specialists such as monarchs who rely on this plant for survival. It's impossible to reflect on the milkweed without also thinking about the animals that rely on this plant and it becomes more difficult to separate the two when their histories are so closely intertwined. ResourcesBascompte J, Jordano P. 2007. Plant–animal mutualistic networks: the architecture of biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 38: 567–593

Dailey, P. J. Graves, R. C., & Herring, J. L. (1978). Survey of hemiptera collected on common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, at one site in Ohio. Entomological News, 89, 157–162. 23 Dailey, P. J. Graves, R. C., & Kingsolver, J. M. (1978). Survey of coleoptera collected on the common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, at one site in Ohio. The Coleopterists Bulletin, 32, 223– 229. Holdrege, C., The Story of an Organism: Common Milkweed, The Nature Institute, (2010). Landry, C. (2010) Mighty Mutualisms: The Nature of Plant-pollinator Interactions. Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):37 Leopold, A. (1989). A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press. This book was originally published in 1949. Leopold, A. (1999). For the Health of the Land. Washington, D. C.: Island Press. The quotes are from the essay “The Farmer as Conservationist,” which was originally published in 1939. Mitchell, R. J., Irwin, R. E. et al. Ecology and evolution of plant-pollinator interactions. Annals of Botany 103, 1355-1363, 2009. Morse, D. H. (1982). The turnover of milkweed pollinia on bumble bees, and implications for outcrossing. Oecologia, 53, 187–196. Southwick, E. E. (1983). Nectar biology and nectar feeders of common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca L. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, 110, 324–334. Wyatt, R., Browles, S. B. & Derda, G. S. (1992). Environmental influences on nectar production in milkweeds (Asclepias syriaca and A. exaltata). American Journal of Botany, 79, 636–642. Wyatt, R. & Broyles, S. B. (1994). Ecology and evolution of reproduction in milkweeds. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 25, 423–441. https://www.fws.gov/southwest/es/Documents/R2ES/Pollinators/8-Milkweeds_Handbook_XerSoc_June2014.pdf |

AuthorRebecca Chandler Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed